Fly Fishing 101: Lifecycle Of The Mayfly

This article is part of a series by Old Town Pro Staff member Megan Hess. Megan is the founder of BeadHead Fishing Company, a guide service and fly tying company based out of Hudson, Maine. She has her bachelors degree in aquatic biology and a masters degree in ecology and environmental sciences. She researched mercury contamination in waterbodies using aquatic insects for 8+ years. She is a Registered Maine Fishing Guide, a commercial fly tyer, and a guide for Chandler Lake Camps and Lodge.

Have you ever opened a fly box and was overwhelmed by the different shapes and patterns of flies? Some of the most common questions I have received are, "Will this fly be fished subsurface or on the surface?", "What does this fly mimic?", "How do I know what fly to use?".

To adequately answer these questions, I need to start by explaining the life cycle of an aquatic insect and the behaviors of the insect during each cycle. Here, I will explain the life cycle of a mayfly as a proxy of the general aquatic insect life cycle and discuss tips on how to match flies to the certain life cycle stages. Of course there are more aquatic insects that are used in fly fishing, like caddisflies, stoneflies, and midges that have slightly different life cycles, but we will focus on mayflies first, as they are the most primitive of aquatic insects.

THE MAYFLY LIFECYCLE

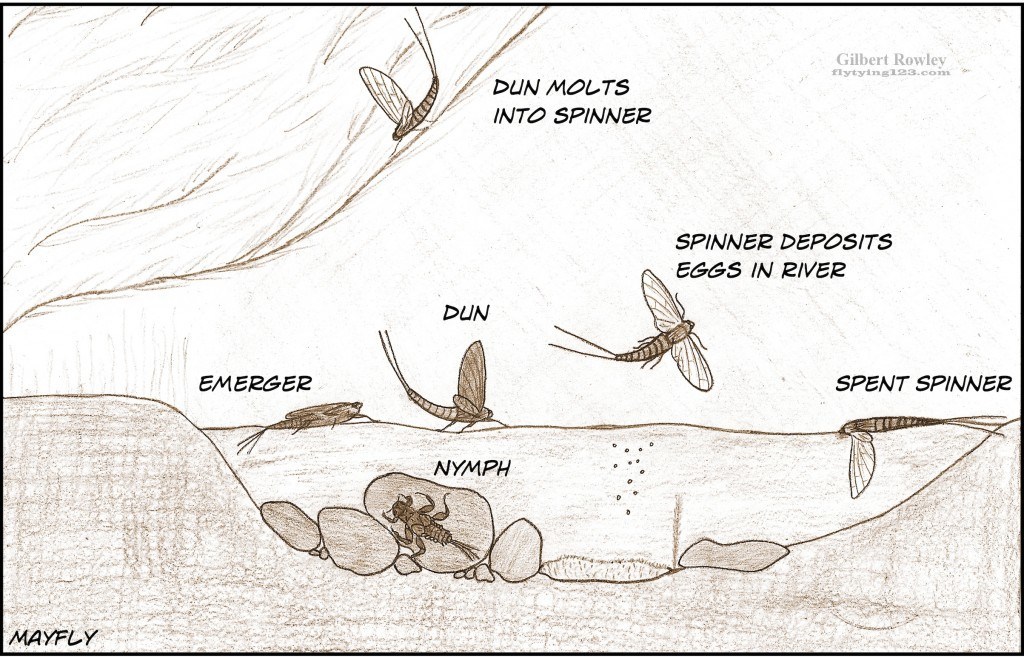

The mayfly life cycle starts in the water and finishes on land. You can think of it as a progression from wetness to dryness. This will be important when thinking about how you want to fish a certain fly in the life cycle. For example, the nymph is fully wet and deep below the surface near the substrate, while the emerger gradually works its way to the surface. The emerger can be fished wet in the water column or dry in the film of the water surface. Lastly, the adult is no longer associated with the aquatic environment (besides laying eggs) and flies around in the air and is fully dry.

Life cycle in scientific terms: Egg → Nymph → Sub-Imago → Imago

Life cycle in angler terms: Nymph → Emerger → Dun → Spinner

Egg

Mayfly eggs are dropped into the water by the adult and sink down to the substrate. A female may produce anywhere from 50-10,000 eggs. Mayfly eggs can be dropped in large clusters, single eggs, all at once, or a couple at a time, depending on the species. On average, it takes about two weeks for the nymphs to hatch.

NYMPHS

Once hatched, the nymphs live on the substrate or interstitial spaces and are primarily herbivorous or detritivorous. The aquatic nymph stage is the dominant life stage with nymphs living on average one year, but can be weeks to months and up to three years depending on species and environmental factors. There are four different behaviors of nymphs including, crawlers, burrowers, swimmers, and clingers. Nymphs will grow and go through a series of moults (anywhere from 10-50 moults) getting larger and larger each moult. An important thing to note as anglers is that nymphs want to be on the substrate as that is their safe spot. If nymphs get swept away in the current, they will immediately try to get back down onto the substrate so they are less susceptible to being eaten by fish. So, in regards to nymphing, a fly fishing technique, you will want to keep your nymph flies near the substrate.

Notice a head region, thorax region, abdomen region, and a tail region in the insect nymph and in the fly. Fly fishing nymphs can be weighted or unweighted (i.e. a bead head) depending on how you want to fish them. A good starting point though is that if a fly has a bead on it, it is supposed to sink and therefore could be used as a nymph. Fly nymphs typically have a larger thorax with some kind of dubbing or bushy-ness to imitate legs. Then they will have a slimmer and tapered abdomen region and possibly a few tails.

EMERGER

The emerger is a very short period of time, seconds, in the life cycle. It is not a life stage, but an action between the nymph and the sub-imago. Once the nymph is fully grown, and the water temperature and sun photoperiod are aligned, the nymph will swim to the surface as fast as possible, crack open their cuticle (shuck) and crawl out as an adult. This is the most vulnerable time for the mayfly during its life cycle.

Most mayfly nymphs use an undulating motion when they swim. This motion is mimicked by using a soft hackle fly that pulses in the water or 'swims'. A soft hackle fly can be used to mimic an emerging mayfly that is swimming to the surface, which can be fished by swinging it and stripping it through the water column. Additionally, a klinkhammer can mimic the nymph that is at the surface and starting to emerge as the adult, which is fished like a dry fly.

SUB-IMAGO (DUN)

The sub-imago emerges from the nymphal shuck on the surface of the water. During this stage, the wings appear dull or translucent and contain tiny hairs that help the adult push off the water quickly (hydofuge). So these tiny hairs help the adult get off the water safely, however, they make the sub-imago a sub-par flier. Sub-imagos are still sexually immature, so they fly to the riparian zone, and within 24 hours, moult into the final adult stage.

IMAGO (SPINNER)

The imago is the final adult stage of the mayfly. Mayflies are the only aquatic insect that has two different winged adult stages. Mayflies need to molt again to reduce larval features (e.g. mouthparts) and expand on mating features (i.e. genitalia). Mayfly imagos have sexually dimorphic eyes and legs, with males having larger eyes and longer forelegs than the females. The imago have mouthparts and a gut, but they serve no function because the adults do not feed. They use all of their energy for reproduction. The imago will now have clear wings with no hairs and are strong fliers which is important for the large mating 'dances'. Adult mayflies are short lived (i.e. hours to days), so large mating swarms increase the chances of mating quickly and efficiently. After mating, the females return to the water and use their last bit of energy to lay their eggs. Female mayflies deliver their eggs to the water in a variety of ways. They will either fly close to the water's surface and drop large clusters of eggs or will have to touch their abdomen to the surface to break surface tension and drop hundreds of single eggs into the water.

This egg laying stage is what we are mimicking when we are fishing dry flies on the surface. Therefore, the dry fly can be presented on the water with a dead drift (no tugging or movement other than the natural flow of the water) or can be picked up and tapped all around the water's surface.

Dry flies are usually very light and have some sort of wrapped stiff hackle to allow the fly to sit on the water's surface tension. Mayfly adults have wings that sit upright and together behind their thorax. So, a good way to tell if a dry fly is designed to mimic a mayfly is to look for upright wings, an Adams or Wulff style fly. Mayfly dry flies will have these upright wings, some hackle wrapped around for buoyancy, a tapered abdomen and some tails to help the dry fly float and balance out the weight of the wings.

It is important to understand the biology of aquatic insects when getting serious about fly fishing. This was a brief introduction to the mayfly life cycle explaining how nymphs emerge into sub-imagos (duns) and then into egg laying imagos (spinners). We also discussed the behaviors of each stage of the life cycle and related it back to how you would begin to fish that stage. Lastly, I briefly touched on how to start to recognize the differences between a nymph, emerger, and dry fly for mayflies.

This article is part of our Fly Fishing 101 series. For more articles by Megan Hess please check out our main blog page.